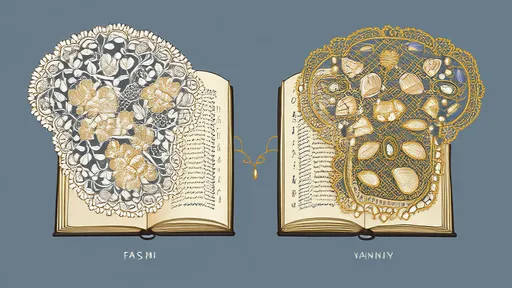

In the intricate world of lace, two names stand out with particular resonance: Chantilly from France and Venetian from Italy. These laces, born from distinct cultural milieus and historical contexts, represent not just textile artistry but the very soul of their regions. The differences between them are woven into their patterns, techniques, and the stories they tell.

The story of Chantilly lace begins in the eponymous town north of Paris, but its true fame was cemented in the 18th and 19th centuries. It is the lace of elegance, of dark sophistication, often created in black silk thread against a delicate net background. The most classic Chantilly pieces are black, though white and ivory versions exist, often used in bridal wear. Its patterns are typically floral—delicate blossoms, scrolling vines, and intricate medallions—outlined with a thicker, silky thread called a cordonnet that gives the design a slight, elegant relief. The background is a fine, hexagonal mesh, and the overall effect is one of exquisite lightness and grace. It was the lace of the French aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, adorning shawls, parasols, and most famously, the lavish gowns and veils of the fashionable woman. It whispers of moonlit gardens, of romanticism, and of a certain Parisian chic.

Venetian lace, by contrast, is a declaration. It is bold, sculptural, and unapologetically opulent. Its origins in the Venetian Republic speak of a maritime empire that was a crossroads of trade, culture, and immense wealth. This lace is not about subtlety; it is about grandeur. Developed earlier than Chantilly, in the 16th century, Venetian lace is needle lace, built from the ground up with a needle and thread, unlike the bobbin-made Chantilly. This technique allows for incredible density and dimension. The patterns are dense, often featuring robust floral motifs, Baroque scrolls, mythological figures, and complex geometric patterns. The texture is raised and varied, with areas of dense stitching (the punto pieno) creating a almost embossed effect. It feels heavier, more substantial. This was the lace of doges and princes, used to trim ecclesiastical vestments and the lavish costumes of the nobility, proclaiming power, faith, and immense status.

The very tools and threads used mark a fundamental divide. Chantilly is a bobbin lace. The artisan works with dozens of bobbins, weaving the linen or silk threads over a pattern pinned to a pillow. The process is one of intricate weaving, resulting in a lace that is fluid and continuous. Venetian lace, specifically its most famous type called Gros Point de Venise, is needle lace. It is embroidered, built stitch by stitch with a single needle, a technique closer to sculpture than weaving. This allows for far greater relief and textural drama. The threads, too, are different. Chantilly favors fine, matte silk, perfect for achieving its signature smoky, shadowy effect. Venetian lace was historically made with glossy linen thread, which caught the light and emphasized the dramatic peaks and valleys of its design.

Perhaps the most striking difference lies in their visual and tactile personalities. Hold a piece of Chantilly lace to the light. It is ethereal, almost like a shadow puppet of flora. It is meant to drape and flow, to complement the form beneath it without overwhelming it. Its beauty is in its delicate precision and its ability to both reveal and conceal. Now, imagine a piece of historic Venetian Gros Point. It stands on its own. It is a statement piece of texture and volume, so substantial that it can form stiff collars or cuffs that hold their shape independently of the garment. It does not whisper; it commands attention. It is art to be worn, a testament to the hours of painstaking labor required to create its dense, relief-heavy form.

Their historical journeys and cultural footprints also diverged. Chantilly lace reached its zenith of popularity in the 19th century, becoming a symbol of the Romantic era. It was immortalized in paintings by artists like Manet and became a staple of high fashion. Its production, though hit hard by the invention of machine lace, saw revivals and remains associated with haute couture and timeless elegance. Venetian lace was the engine of a vast economic industry for the Serenissima Republic. At its height, it was so valuable and coveted across Europe that the government feared the export of techniques and talent would ruin their monopoly, leading to secretive workshops and even legislation to protect its secrets. Its decline was more precipitous with the fall of the Republic, but its techniques form the bedrock of needle lace traditions and it is still revered as the pinnacle of sculptural textile art.

Today, the legacy of both laces endures, but in different spheres. Authentic Chantilly lace, especially the black silk variety, is a rare and precious find, still produced by a handful of dedicated artisans and prized by fashion houses for its unparalleled romanticism. It remains a symbol of French elegance. Venetian lace, particularly the historic techniques of Gros Point and Point de Venise, is preserved as a cultural treasure on the island of Burano. The lace made there today is a direct link to that glorious past, a tourist attraction and a testament to human artistry, though much of what is sold is now machine-made imitation. The true, hand-made pieces are museum-quality artworks.

In the end, the difference between Chantilly and Venetian lace is the difference between a sonnet and an epic poem. One is a masterpiece of delicate suggestion and nuanced beauty, a breath of romantic elegance. The other is a monumental work of bold form and dramatic intensity, a powerful testament to art and ambition. Both are sublime achievements of human creativity, but they speak in entirely different visual languages, forever telling the stories of France and Italy, of the pillow and the needle, of the whisper and the declaration.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025